New findings could help children with growth disorders

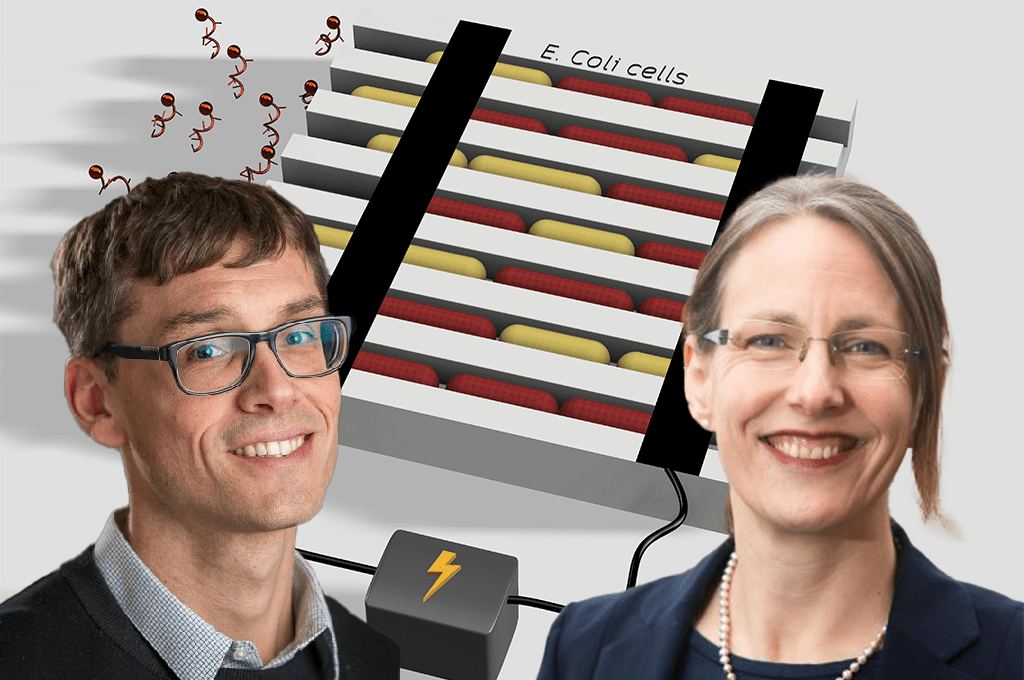

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet have discovered that bone growth in mice functions the same way new cells are being produced in blood, skin and other tissue – not a fixed number of “growing cells” that run out and we stop growing, as previously thought. The study was enabled by the SciLifeLab National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI).

For bones to grow as they should, stem-cell like progenitor cells called chondroprogenitors need to produce cartilage cells, chondrocytes. The previous view of progenitor cells was that they are present in limited numbers, formed during embryonic development. The idea has been that these cells eventually run out and that we therefore stop growing.

The study, published in Nature, now shows that this may not be entirely accurate – at least not in mice. The researchers found that dramatic changes in cell dynamics occured after birth, the progenitor cells had acquired the ability to regenerate. This is the case in for example skin and blood, but now seems to be a reality when it comes to bone growth as well.

“If it turns out that humans also have this growth mechanism, it could lead to a significant reassessment of numerous therapeutic approaches used for children with growth disorders. The mechanism could also explain some previously puzzling phenomena, such as the unlimited growth seen in patients with certain genetic mutations”, says Andrei Chagin, research group leader in a press release by Karolinska Institutet.

Read the press release from Karolinska Institutet: In Swedish or English.