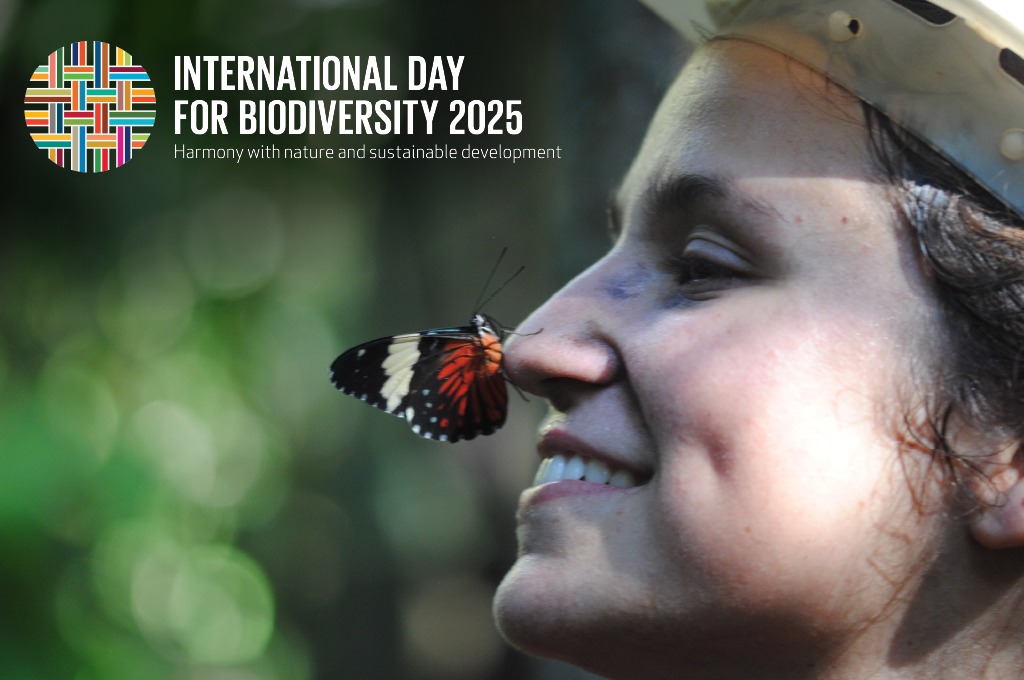

Evolutionary history of Tuatara clearly mapped for the first time

The genome of the tuatara, a reclusive species of reptile endemic to New Zealand has been mapped by an international team of scientists, among them Alexander Suh’s team at SciLifeLab and Uppsala University. The species diverged from its closest relatives and created its own phylogenetic branch over 250 million years ago. The findings, now published in Nature, reveal that the tuatara has more genes that protect against age-related damage than any other vertebrate species.

This is the first time that the tuatara’s genome has been sequenced and the researchers were able to clearly confirm that its evolutionary history and genetic architecture are unlike most other animals.

From the article: “A key link to the now-extinct stem reptiles (from which dinosaurs, modern reptiles, birds and mammals evolved), the tuatara provides key insights into the ancestral amniotes”.

As the tuatara diverged from all their relatives between 150-250 million years ago, its phylogenetic position has been debated for a long time. Some have argued that the species is more closely related to birds, crocodiles, and turtles, while others mean that it is related to lizards and snakes. This study has been able to show that the tuatara is in fact related to snakes and lizards, but diverged and created its own evolutionary branch approximately 250 million years ago.

Alexander Suh (SciLifelab/Uppsala University) and his research group is co-affiliated with SciLifeLab and support genome consortia like the tuatara genome project and colleagues at SciLifeLab with expertise on how to annotate repetitive elements. Alexander and his group at Uppsala University who were engaged in the study, focused on a specific type of transposons, or jumping genes, that can copy-paste themselves around the genome. Contrary to other amniotes (birds, reptiles, and mammals) the tuatara has a large number of jumping genes, which explains why its genome is 67 percent larger than that of humans.

“Overall, the repeat architecture of the tuatara is—to our knowledge—unlike anything previously reported, showing a unique amalgam of features that have previously been viewed as characteristic of either reptilian or mammalian lineages. This combination of ancient amniote features—as well as a dynamic and diverse repertoire of lineage-specific transposable elements—strongly reflects the phylogenetic position of this evolutionary relic.”, the researchers conclude in the report.

“We annotated repetitive elements that include transposons of the tuatara. Large genomes such as this one usually contain large amounts of repetitive elements and annotating these is a key bottleneck in genome research these days. Not surprisingly, we found a lot of transposons in the tuatara genome, but surprisingly, these were very diverse and many were “jumping” on recent evolutionary timescales”, says Alexander Suh.

The tuatara is long-lived and can live for more than a century. This fascinated the researchers who decided to look for genes that provide protection from age-related damage. They found that the tuatara had more such genes than any other species of vertebrate known today. They also looked at genes for sight, smell, and temperature regulation to find out why the tuatara is so resistant to disease.

“For me, the main uniqueness of the tuatara genome project was how global this collaboration was. We were three research groups coordinating the repetitive element annotation efforts between each other across timezones, which was both fun and challenging. In the end we used a combination of three complementary approaches to repetitive element annotation which can help in future genome projects.”, says Alexander Suh.

This sequencing of the tuatara genome provides a foundation for future studies of its unique biology, which contributes to our understanding of amniote evolution.

Read the Uppsala University press release here (in Swedish).

Photo: Nicola Nelson